Playing together in the pandemic: Using Jamulus for Internet

jam sessions

As

we move into winter, we're being told that it's vital we all stay

socially distanced. After a summer and mild fall when we've been able

to get together and play music outdoors, we're facing a long few months

when that option is not available. How do we avoid the temptation to

gather for a few hours in someone's house, singing and playing? Maybe

the internet can provide an answer.

At first, this sounds

impossible. Anybody who's tried to sing "Happy Birthday" to a

participant in a Zoom conference call knows the problem. You sing to

the voices you hear, but it seems they're singing at a different time,

and everything falls apart. If you've tried playing music across a Zoom

or Skype call, you know the same thing happens: it's impossible to

synchronize your parts.

The problem is latency,

the time it takes for sound to be converted from analog waves to

digital form, sent through the various pieces of hardware and network

connections, and converted back into sound at the listener's end.

Programs like Zoom, combined with standard computer audio processing

hardware, need about a half second to get sound from here to there, and

that half second is deadly for singing and playing together. In the

physical world, it takes sound about a thousandth of a second - one

millisecond - to travel one foot, so that half second is the equivalent

of trying to synchronize with someone 500 feet away - if you could even

hear them!

We do deal with latency in the physical world, of

course. We don't stand in exactly the same spot as the people we're

playing with, so we are used to dealing with a small amount of latency

in jam sessions. Even in small picking circles, people stand ten feet,

or ten milliseconds, apart. In big sessions, that distance may be

twenty feet or more. In fact, we can play pretty well with delays of up

to about thirty milliseconds. Still, that's a far cry from the 250-500

milliseconds encountered using standard conferencing software.

But people can

play on the Internet. Click the image below to hear the session

captured in the screenshot, with over 20 people singing together:

Jam software: Jamulus

This page is going

to focus on Jamulus, a free program designed to allow lots of people to

play together. The screenshot and recording above were taken from a

Jamulus session. The rest of this page takes you through a step-by-step

process for downloading, installing and setting up Jamulus, and

optimizing it for the best possible playing experience.

Jamulus is an open-source program designed

specifically to allow musicians to play together online. Unlike similar

programs like JamKazam, it depends on a server to tie musicians

together; for this reason, it allows much larger groups to connect and

play than JamKazam does.

The

page is broken down into units, each of which will take you a step

further toward the goal of playing with your friends again:

Step 1: Download and install the program

Step 2: Getting used to the program by listening to someone else's session

Step 3: Playing into Jamulus: trying a solo session

Step 4: Playing with others!

Step 5: Tuning your connection for the best possible sound with your existing equipment

Optional Step 6: Upgrade your equipment to make playing with others a better experience (or even possible).

If you know what you're doing and want the quickest possible explanation of how to get Jamulus running, here's the official Jamulus onboarding Wiki page.

Finally, a technical explanation of what's going on here, and what makes this program work when mainstream programs like Zoom can't.

Experimenting with Jamulus, Step 1: Setup

If

you're just interested in trying Jamulus out, you can do so by simply

installing and running the software. If you're using

a standard

computer configuration - WiFi, internal sound card and the like, you

won't get the best experience, but you can play and hear yourself. You

can also listen in on other people's sessions, which is generally

allowed unless the session is marked "private".

Download

the Jamulus installer from here. If you're running on a

Windows computer, you'll also need ASIO4ALL. Mac users are encouraged to install the optional program QjackCtl. Turn your speakers and

microphone on, run the installer and double-click to start Jamulus.

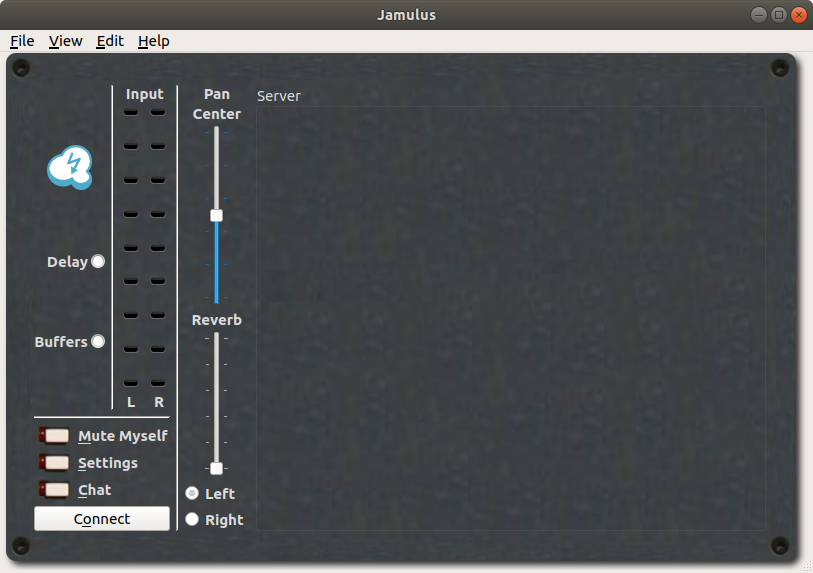

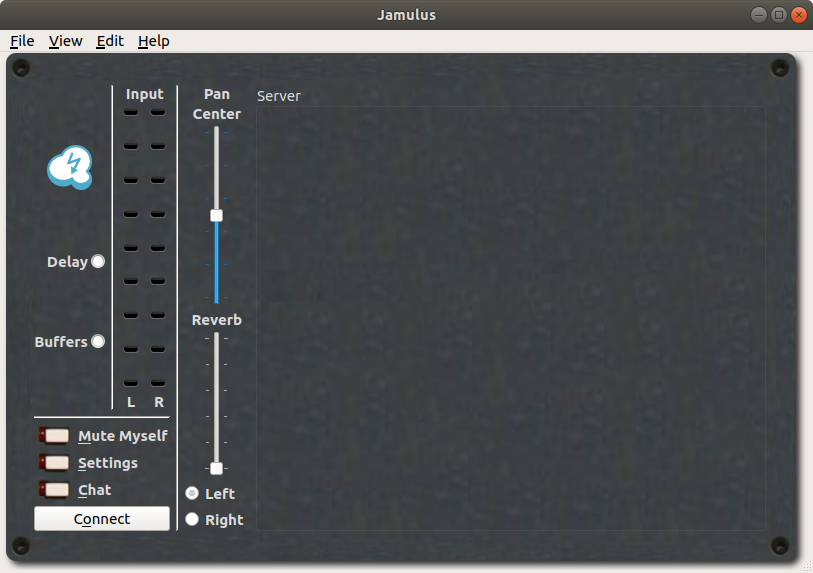

You'll see the Jamulus mixer, which looks like this:

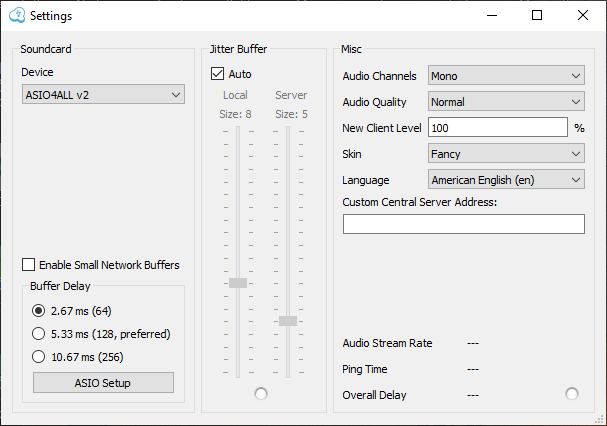

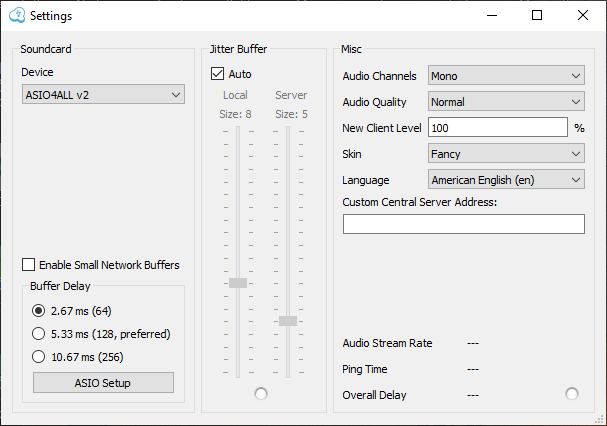

Press the Settings button and you'll see this menu pop up (Windows):

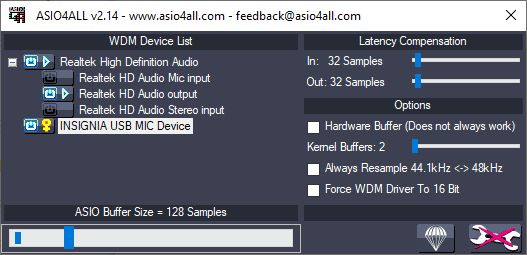

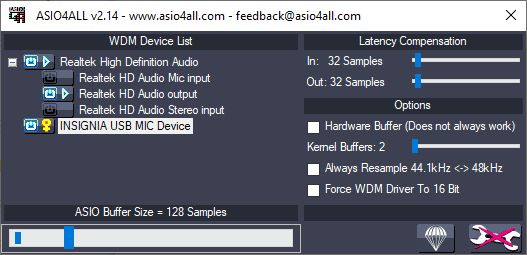

ASIO

Setup is where you'll find critical controls for minimizing latency.

Click on that button at the bottom of the menu, and you'll see an

additional menu:

The

critical setting on this menu is the ASIO Buffer Size slider on the

bottom. This should be set as low as practically possible. This setting

is your first foray into the tradeoff between latency and quality - set

it too low, and your signal will sound like you're playing underwater;

too high, and the extra delay will make it very hard to play with other

people. If you can set it to 64 and get good results, you're minimizing

the amount of latency that the Jamulus sound processing software adds

to the overall setup.

Most people will be able to use 64 or

128 samples, a difference of almost 3 milliseconds in overall delay.

Experiment and see what you can get away with.

The second

important setting on this screen is the WDM device list. If you have

only your internal sound card to choose from, you will only see one set

of devices. If you have plugged in external USB speakers or a USB

microphone, you will see more entries in the list. In the screen above,

the Realtek HD Audio board shows one input (the built-in microphone in

the laptop) and two outputs, one mono and one stereo. This computer has

an Insignia external microphone plugged into a USB port, and that shows

up as a separate entry in the list. You can turn individual inputs and

outputs on and off by clicking on the on/off icon and the play icon

next to each. They are mutually exclusive - turning the external mic on

will turn the internal mic off.

The third sometimes useful setting is the

"Always Resample" checkbox on the right hand side. You can usually

ignore this, but if you connect to a jam session and find that your

sound is significantly out of tune with everyone else, no matter what

you do, the problem may be incompatible sampling rates. Everyone in a

Jamulus session should be set to 48kHz. If someone manages to connect

at 44.1kHz, you can try checking this box. Otherwise, you can

safely ignore it.

Now

that you've got everything configured as well as possible (for now),

it's time to connect to a server and test your setup with a solo

session.

Back to index

Step 2: Making a test connection - getting used to the

controls and listening in on a session

Before

continuing, you need to be aware of how the Jamulus universe works.

Virtually everything on the Internet operates on the basis of

individual identity. You can't use a service without providing and

verifying an email address and logging in. The services you connect to

are vetted and set up behind layers of security. This system keeps

everyone safe.

Jamulus

doesn't work that way. Anyone can set up a server, and anyone can

connect to it without providing any clue to their identity. If this

seems dangerous, realize that it can be - but it works because Jamulus

users trust the community of other musicians who use the Jamulus

service. It would be terrifically easy for a small number of jerks to

tear down this system of trust, either intentionally or through

ignorance of the rules, so it's vitally important that you understand

what is OK and what is not OK.

Above all, be polite, use common sense, and don't be that guy.

The

Internet is full of Jamulus servers. Some are chock-full of

people

making music together. Others are just waiting around. In this step,

you'll drop in on other people's sessions to see how well your system

works for incoming sound. You'll have to wait to test your microphone

and the overall performance of your system until the next step.

To start this test, run Jamulus. You'll need to set one critical

parameter before trying to connect: turn on the Mute Myself

button so the orange light next to it glows. This will allow you to

connect to a running session without being heard by the participants.

In the world of Jamulus, listening in is considered OK; making

distracting noises because your microphone is live is not. You'll know

you're muted if you see a big orange banner at the top of the jam

window that says:

MUTED

(Other people won't hear you)

For this test, don't proceed unless you see that banner.

Warning:

When you connect to a server, look for a banner near the top that says

"[Recording active]". Muting your channel will keep other people from

hearing you live, but your input will still be recorded. So if you plan

to yell at the dog or give someone your credit card number over the

phone, it's best to disconnect from the session entirely.

If the session is not being recorded, your voice will just vanish into

the ether.

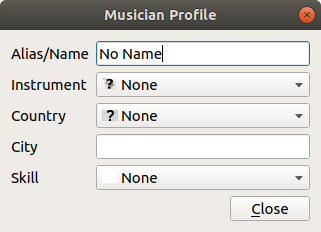

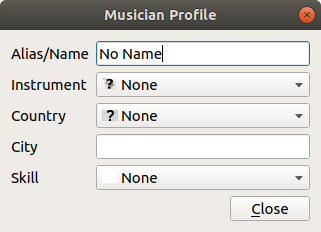

It's also polite to let people know who you are. To set your identity,

open the View

menu, click My Profile...

:

Fill in the relevant information. For now, since you're not actually

going to be participating, enter Listener

as your instrument. Your skill level is also unimportant now; when you

fill it in later, it will translate to a color code in your section of

the jam screen.

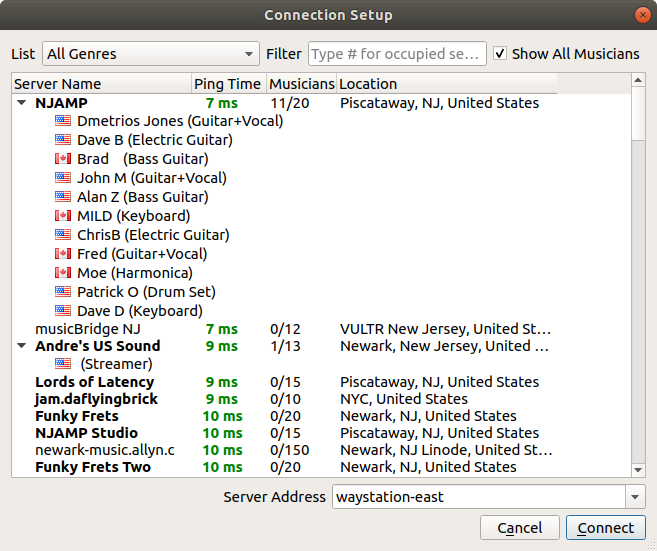

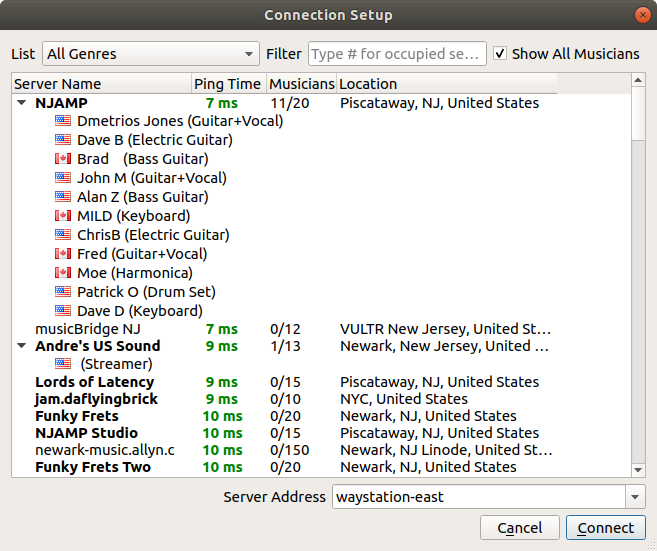

Now that you've identified yourself, tap the Connect button. You'll see

a list of available servers:

The

servers are computers that are run by individuals. There are no

qualifications to run one; you can select "Jamulus server" in

your

system's app menu and do it yourself. There are also no qualifications

to put your server on the public list, although there are some settings

outside of Jamulus that have to be set before anyone but you can see

your server. Setting up a Jamulus server is outside the scope of this

page.

On the list you will see each server's name and location. You'll also

see a measurement in milliseconds (ms) called ping time.

This is the time it takes data from your computer to reach that server,

and is a direct component of the latency you will encounter when you

connect to that server. The bigger the number, the more delay you will

hear when you play with other people on that server. When you're trying

to find people to play with, this will be a critical factor - you'll

ideally want to keep total latency below 30 ms so your playing sounds

coordinated with everyone else's, both to you and to them. However,

since you're just listening for now, this number is unimportant. You

just have to hope that the people in the session are in sync with each

other.

Some of these servers have a list of participants. These

are the ones you want to focus on. Try to find a server that has more

than one or two; some people leave themselves connected to their server

all the time, even when they're not playing, and if you connect to them

you won't hear anything. A big list shows an active jam, and that's

what you're looking for to run this test. Avoid connecting to servers

that have "Private" in the name - those people don't want strangers

listening in. Nothing will stop you from connecting, although you will

probably be asked to leave, but, again, don't be that guy,

remember?

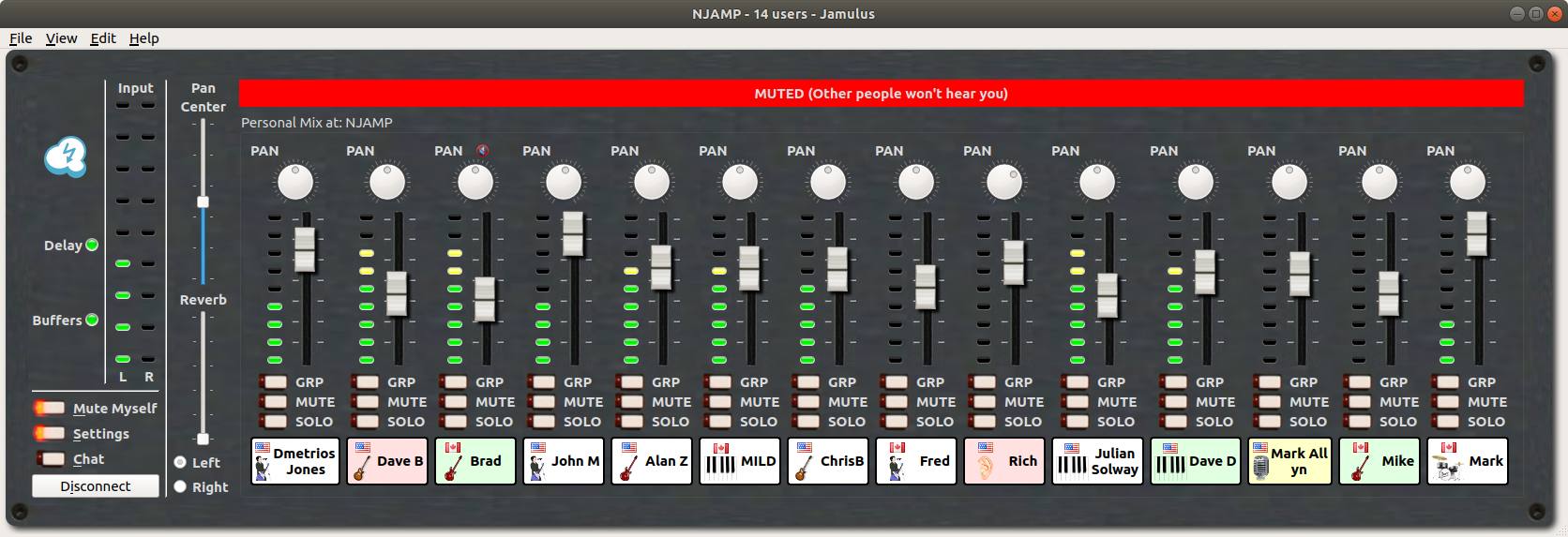

Put

on your headphones (wired only, please) and pick a jam from the list. I

connected to the NJAMP session in the list above, and immediately heard

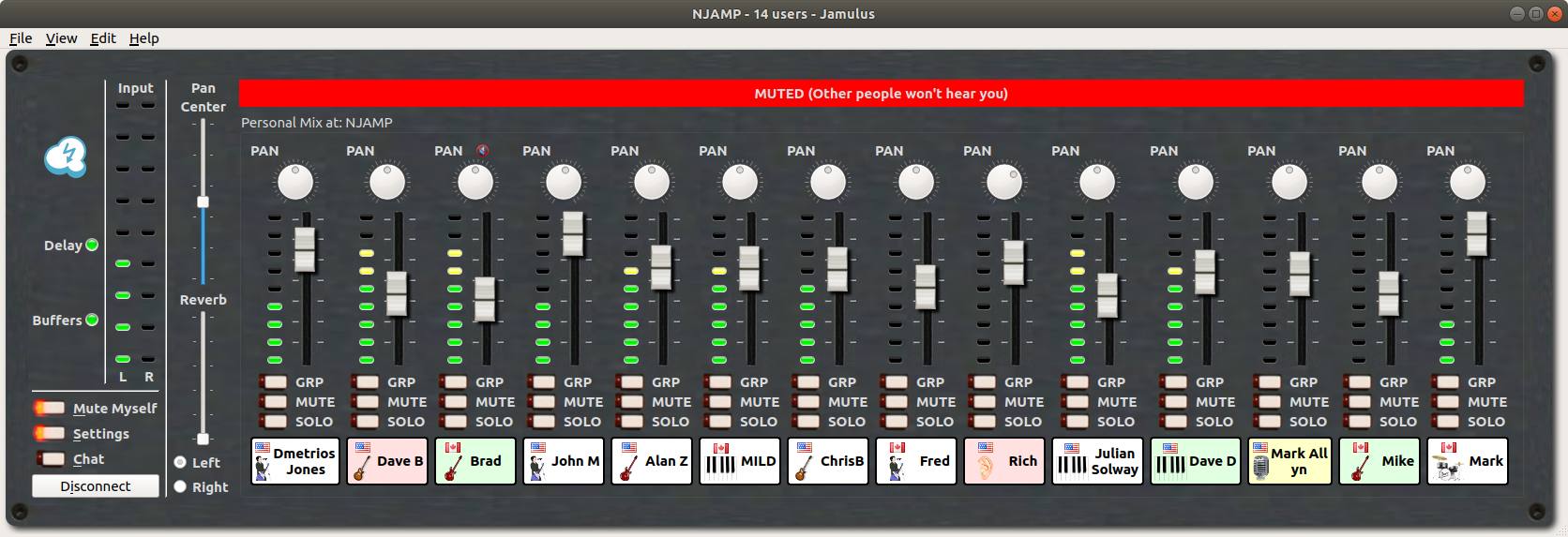

the session and saw this display:

This is the control panel for the jam. It shows your personal mix

of the session. You can adjust these controls to make the musicians

sound however you want - it won't affect what anyone else hears. From

top to bottom, each channel

has a control for

pan (move the channel between your left and right ear), volume, group

(a more advanced feature; don't worry about that one for now), mute

(turn that channel completely on or off), and solo (listen to that

channel only). Play with these controls until you get used to them -

remember, nothing you do will affect what anyone hears, other than you.

The green VU meter next to the volume fader shows which channels are

active. In a big session they, along with the instrument icons in the

name boxes, can help you figure out which channel to bring up or down

to focus on a particular sound.

You may notice that you hear

noise besides the musician on some of the channels. The noise may be

clicks, pops, or an "underwater" sound. This is a sign of incorrect

channel settings - either dropouts (the network is too slow to handle

the amount of data being sent) or buffer overruns (the source computer

is processing data too slowly to keep up with the sound). In either

case, the problem is on that channel, and there's nothing you can do to

make it sound better. You'll have a chance to adjust these settings in

the next section, so your signal is nice and clean for the people who

are listening to you.

If you have gotten this far, you are proficient at the listening part

of Jamulus. You're halfway there.

Back to index

Step 3: Playing into Jamulus

Now

that you know you can hear a session, it's time to try your microphone,

and to get used to what a little latency sounds like.

To set

up for this experiment, change your profile instrument from "Listener"

to whatever you play. If you're a vocalist, there are settings for that

too. Turn off the "Mute Myself" button so you hear yourself, and make

sure your microphone is connected and turned on, if it has a switch.

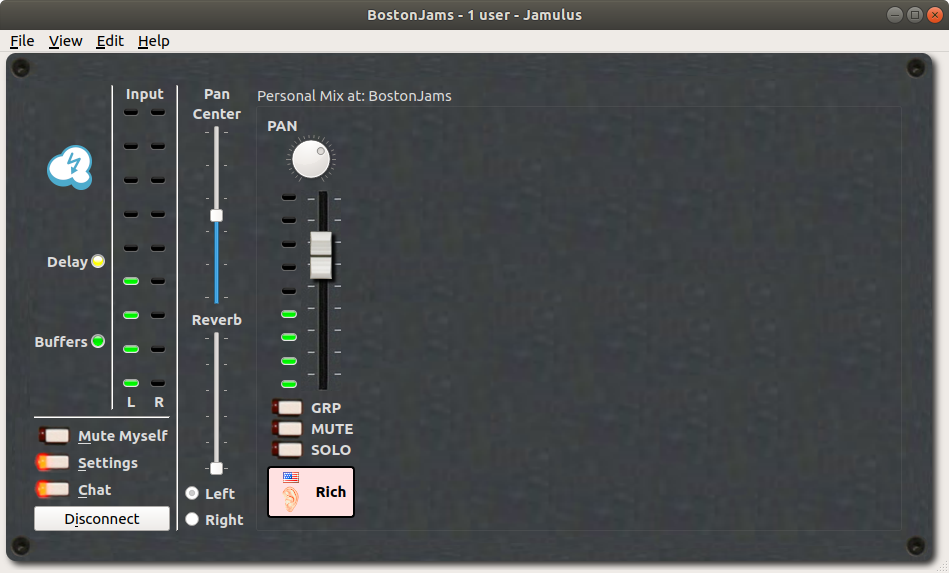

For

this test, click on Connect again. You'll want to find an unused server

with fairly short latency. You're free to use anything that's out

there, although if the owner shows up you may be asked to leave - or to

become part of a session! In the server list, click on your chosen

server's name, and click on the Connect button at the bottom of the

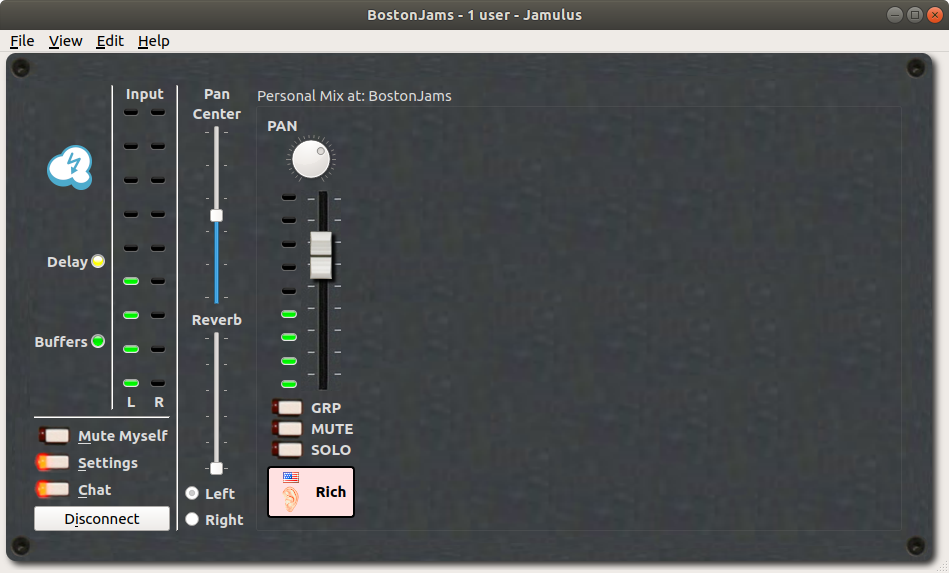

window. You should see one channel in your personal mix:

Tap

on your microphone. You should see the green lights on your channel

bounce up and down, and you should hear the tapping sound in your

headphones. If you do, you've successfully made a connection. You need

to learn how to adjust your channel for the best sound quality and

shortest latency, but you have successfully played music into the

Internet.

If you don't hear anything, and all the lights are

dark on your channel, you may need to check your input settings (see

"ASIO setup" above), to make sure Jamulus is listening to the same mic

you're talking through. If the mic is powered, make sure the power

source is on or the batteries in the mic are good. You should also make

sure your mic is turned on and connected to the correct port on your

computer. If all else fails, try using your mic and headphones with

some other recording program, like Audacity or your system's sound

recorder. Both Windows and MacOS have sound control panels that provide

visual confirmation that your microphone is receiving sound, and that

generate test sounds that you can hear through your headphones. You can

use these to make sure that everything other than Jamulus is working

correctly.

If the green lights on your channel are bouncing, but

you still don't hear anything, the mic is probably working correctly.

Check your sound output - is the volume turned up? Are the headphones

plugged in correctly? Is ASIO set to use the correct output channel?

Back to index

Step 4: Playing together

Now

that you've got all your equipment tested, it's time to try the real

thing! Contact a friend or two or more. Actually, you might want to

start with fewer just because there's less to go wrong. It isn't really

more complex to run a session with lots of people, but if one person

has a problem - feedback, for example - it can spill over into

everybody's experience. If you're doing a short test, find a nearby

unused server (nearby defined by short ping time), hop on, and try

playing together. Every guide to using Jamulus recommends turning off

the local monitor, the thing that lets you hear your own signal before

it makes its round trip to the server. If you're singing or playing an

acoustic instrument, you hear yourself through the air, so this is not

quite as useful, but still worth doing so that you minimize the

confusion of hearing your own sound twice because of the echo. You can

do this by pressing the Mute button on your channel or by sliding your

fader all the way down to zero.

Once you've connected, you

should be ready to go. You've already practiced using all the Jamulus

controls in the previous sections. Adjust your mix using the faders.

Separate your sound from others with the Pan dial at the top of each

channel. Add a little sheen of reverb to the whole system. Most

important, use the buffer size and jitter settings on the Settings

panel to achieve a usable balance of delay and quality. Too much delay,

and you'll find your playing slows down as you try to stay in sync

because the music of other people arrives too far behind your own. Too

little quality, and the sound will be unlistenable. Step 5 will take you through some of the adjustments you can make.

If

you can't manage to get your connection tuned and playable, all is not

lost. It's very possible that you can upgrade your equipment to improve

both quality and delay. Check out Step 6 for a list of things you can try. Some of them are even free, or very close!

If

your connection works, on the other hand, you're all set! Look around

for sessions you're compatible with, and use the festival jam session

protocol - enter as a listener, with your mic muted, and decide if you

fit in. If you think you will, unmute yourself, say hello, and ask

permission to join.

If you really want to control your jam

opportunities, it's fairly easy to set up a server even on your own

computer, and invite your friends in. That's outside the scope of this

page, but if there's enough interest I'll put that up too.

Back to index

Step 5: Tuning your connection

Running

these tests should get you to a working system. You should be able to

speak or play into your microphone and hear yourself through the

headphones.

In an

ideal world, there should be so little time between producing a sound

and hearing it that the two are simultaneous. In the real world,

however, there's lots happening, and all of it takes time.

(TL;DR: the next

paragraph contains stuff you don't actually need to know, but that will

make it easier to understand the things you will need to know. You can

skip it if you want.)

You

play into the microphone. The sound is translated into a digital

signal. The signal is broken up into small sections, or packets, that

can be sent over the Internet. The packets are sent to your home router

as data. The router sends each packet to the Jamulus server, possibly

by a different route for each packet. The Jamulus server's router

receives the packets, reassembles them into data, and sends them to the

server. The server collects your data, combines it with the data from

all the other session participants, and sends it back out to you. Now

the data has to make the same trip in reverse, be processed by your

Jamulus app, and translated back from digital form to sound so you can

hear it in your headphones.

(End of geek stuff. You

need to read what comes next.)

The

magic of Jamulus is that it can accomplish everything you need to hear

your music and your session mates' music in a short enough time - under

20 milliseconds, not counting the network ping delay - to allow you to

play as if you're in the same room. In contrast, conferencing programs

like Zoom take between 200 and 500 milliseconds to move sound over the

same network path. You may have to make a few adjustments to make

things work, though.

Picking your session

The

first thing you need to know is how to choose a session that has a

chance of working for you. This is what the ping time is for - it

measures the one part of the system you can't improve, the time

required for a signal to travel from you to the server and back again.

You can choose equipment that speeds up your sound processing, but the

ping time is determined by the network distance between you and the

server, and the most immutable law in the universe: the speed of light.

Quality vs. latency

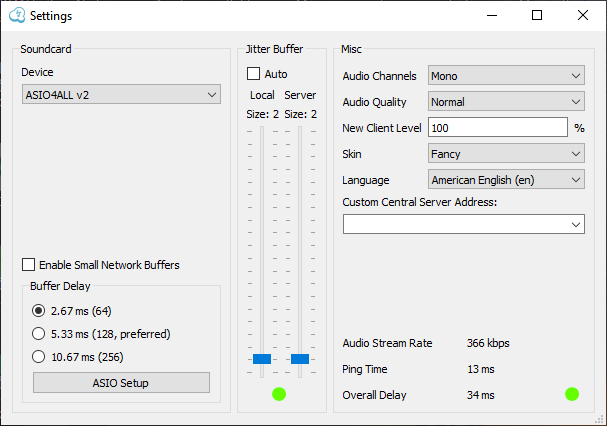

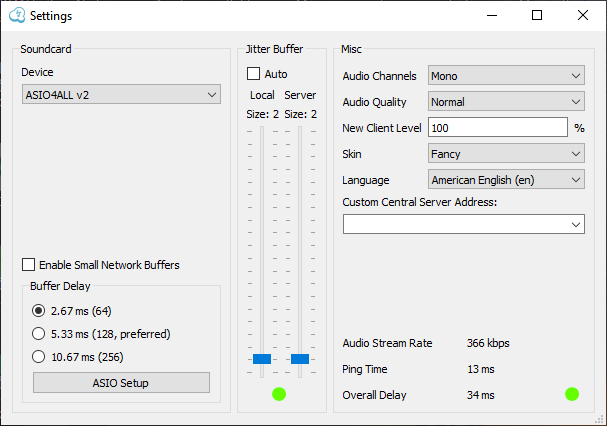

You'll want to go into the Jamulus settings panel to see

what you can tweak. Here's what the panel looks like when you're

connected to a session in Windows (the Mac panel will be similar):

There

are a few things to be aware of on this screen. First is the buffer

delay in the lower left corner. This parameter, which you can set, has

a direct impact on your delay time. It also has a direct impact on your

sound quality - a classic tradeoff of quality for speed. Set it too

high, and you'll hear the echo delay increase; too low, and you'll get

that "underwater" sound that indicates buffer overruns. How much

distorted sound you're willing to tolerate in the name of delay - which

can make or break your ability to play in the session at all - is up to

you and your jam-mates, since they will hear the same distortion you

do. You can experiment in your solo session, and hear the effect of all

these changes.

In the center of the screen is the jitter

buffer control. Like the buffer delay, the jitter buffer adjusts the

amount of time the network is allowed to process the sound you're

making and hearing. Also like the buffer delay, it allows you to trade

speed for quality - lower values of these sliders means a faster

network, but more potential for overruns and the "underwater" effect.

If your network is fairly fast, it's best to keep this setting on Auto

using the checkbox at the top. That will allow Jamulus to adjust the

buffers to respond to temporary changes in network traffic. If the echo

delay caused by latency is close to your limit, turn Auto off and

adjust the sliders by hand. You'll hear the effects immediately.

You

will also notice the green dots at the bottom of the window. These dots

measure latency objectively, and will turn red if Jamulus thinks your

signal delay is too long. In general, alternating red and green is

tolerable, but solid red will probably be unlistenable for you and

everyone else. Adjusting the settings discussed above will have a

direct impact on these lights; use them as a rough guide, but trust

your ears above all.

There is one other adjustment you can make

on this screen, "Enable Small Network Buffers". As a rule, leave this

off. We've never seen it improve the performance of a connection.

The

numbers in the lower right section of the window show you the results

of all this adjustment. Ping Time is a live measurement of the time a

signal needs to travel the length of the connection. It is unaffected

by any changes you make, and will stay more or less constant as long as

you stay connected to the same Jamulus server. Use it as a guide to

whether a server is worth trying to connect to - ping time over 20ms,

added to all the signal processing your computer performs, will

probably be too long to be usable no matter how you tune your settings.

Note: this number will probably vary

by 5ms or so as you watch it. If you see giant changes - for example,

15ms to 50 or 60ms for a short time - make sure you're using a wired

internet connection. That kind of variance is a sign of a WiFi

connection.

The other two numbers on this screen are for

information only. Overall Delay is calculated based on assumptions

about your equipment. It is an approximation, not an actual

measurement, and it changes in lockstep with the Ping Time. If you use

your computer's internal sound hardware, your actual delay will

probably exceed this number; if you use a really fast external

interface like the Focusrite, it can be significantly shorter.

For more information and the official guide to Jamulus controls, check this document at jamulus.io.

If everything is configured well, you should now be able to click the Mute button on your channel (not

the "Mute myself" button at the left side), speak or play into your

microphone and hear your sound, processed by the server and returned to

you, in your headphones. You can experiment with the fader to change

the volume of your channel, and the Pan dial to move yourself from one

ear to the other. You will be able to do that with every channel in a

live session - remember, those adjustments only affect what you hear.

You can also add reverb to the overall signal, and if your microphone

is stereo (or you have two microphones) you can adjust the reverb and

balance of your signal using the Reverb and Pan controls on the left

side of the screen - those adjustments will be heard by everybody.

You

have now successfully configured the input and output functions of

Jamulus, and your live session is as good as your equipment can make it.

Back to index

Step 6: Improving your equipment

You

knew this was coming, right? Now that you can play online, there has to

be something you can do to make the experience better. I've tested all

the equipment in this list. I'll be happy to post whever works for

anyone else.

Remove all wireless connections.

No bluetooth microphones or speakers and no WiFi internet. If you're

close enough to plug an RJ45 cable into your internet router, do it.

You can buy one from Amazon here,

in whatever size you need. If you have to buy a 100 foot cable and run

it upstairs to plug into your router, it will be worth it.

Move audio processing out of your computer.

This means plugging external sound devices into your computer instead

of relying on the internal sound card, which is almost never designed

for fast audio. It is especially important on the input side - the

built-in microphone in most laptops is one of the biggest fixable

sources of latency in your computer. On the output side, make sure

you're using wired speakers - Bluetooth will provide guaranteed delay.

Needless to say, your external microphone must be connected to the

computer by wire, as well.

It is possible to fix the input side with a low-end USB microphone like this one

for under $25. This microphone should shave at least ten milliseconds

off your round-trip time, especially if you're running a laptop. Tested

and working with Windows 10. Does not work with Ubuntu Linux. Not

tested with MacOS.

The pro approach to fixing both input and output is a digital audio workstation (DAW) like the Focusrite Scarlett 2i2.

That will give you the most flexibility on inputs and outputs. It will

give you the absolute minimum latency, both because the sound

processing hardware inside is optimized for speed, and because you will

be able to use the smallest possible buffer delay value in the Jamulus

settings. This will be 64 frames or 2.67 ms on a Windows or Mac

computer. The Scarlett also allows you to plug in two microphones and

gives you good old-fashioned dials for controlling your input and

output sound. Output can be through standard headphones, or sound

system speakers, or both at once. To use this box you'll need to buy a

pro microphone like the Shure SM-57, and a cable

to connect it with. If you already own sound system equipment for a

band or other PA, you probably have a mic and cable that work. The

Scarlett will set you back about $160, the mic about $90, and the cable

another $10.

Finally, if you have a low-end network connection

and see bigger ping time numbers than your jam-mates, you can talk to

your Internet service provider about upgrading your network speed, or

change providers entirely. Some providers are intrinsically slow (Dish,

Charter and RCN are frequent offenders) while others like FiOS are

built for speed. This is not an endorsement of any particular ISP, so

shop around.

Back to index

Tech geekery: Where latency comes from, and how to fix it

In

a real-time connection, latency is introduced in several places. Here

they are, in rough order of their impact and possibility of fixing:

- Conferencing software. This is the big

kahuna. Standard

videoconferencing software like Zoom and Skype work fine for normal

conversations, where people talk in turn. Because they are not designed

for everyone to talk at once, they sacrificelatency to get better

quality. Cell phones do the same thing - if you call or Zoom someone

within earshot of your phone, you will hear a significant delay between

your speech and the sound from the other end of the connection. If you

try to count along with someone on the other end of a call, you'll find

it's impossible for both of you to line up your numbers.

In conversation this is a minor annoyance - we're used to knowing how

long to wait after the other person has stopped talking before we

start, and that extra fraction of a second can throw us off. In music,

it's deadly, as described above. To make that delay short enough so

playing music is enjoyable, you need software that is designed to make

latency as short as possible without turning the sound into a mass of

dropouts, buffer overruns and other noise.

Fortunately, there are several programs like Jamulus

and JamKazam

that can accomplish that, and many of them are free to use.

- Home

network. Your

local router and network interface introduce

a certain amount of latency. This can be minimized by using a wired

Ethernet connection plugged directly into your router, instead of WiFi.

WiFi is not only slow, it's inconsistent - the amount of delay it adds

can double or triple from moment to moment, making the signal even more

unreliable. A wired connection is fast and steady.

- Audio

connection. Like

the network, wired is better than

wireless for both headphone and microphone connections. No Bluetooth -

use wires.

- Signal

processing gear.

If you're used to talking into the

built-in mic on your laptop, you

should realize that the sound card in there is not designed for speed.

There are external sound interfaces for about $150, or even cheap USB

microphones for about $25, that will speed up your connection.

- The

Internet.

There's

not much you can do to improve the way your audio signal travels across

the Internet. Some people might be able to upgrade their network speed

or change providers, but the majority of the delay here comes from the

simple fact that it takes time for data to move around the country. It

helps to have everyone involved close together - you're not going to

have a good experience jamming with folks across the country or across

the ocean - but a bunch of people clustered around Boston, New York or

even Washington, D.C.can have a surprisingly good time.